I made a mistake yesterday, so now you’re gonna pay for it. Feeling a little sleepy after a workout and a chicken curry for lunch, I wrote a quick bit for my personal blog about the story bible I’d been working on for the Axis of Time series. Then, full of curry chicken and runaway blood glucose, I accidentally mailed it out to about ten thousand people instead of posting it to my widely unread personal blog.

I feel bad about this, because I don’t like to clutter up people’s inboxes with my nonsense. But enough punters wrote back to say they enjoyed the unexpected insight into my process that I decided, why not? I’ll…

No… wait, I’ll write an essay about story bibles!

Wait a minute, JB. What even is a story bible?

Well, grasshopper, it’s a sort of how-to manual for storytelling within a particular narrative world. It stops you from accidentally turning your protagonist’s green eyes blue halfway through Chapter 9, or forgetting whether your fictional kingdom has a monarchy, a technocracy, or one very large, very angry anthropomorphic goose in charge of everything.

The term “series bible” originated in the TV industry in the mid-20th century, when scripts were bashed out on Olivetti typewriters by sad men in sweater vests. These early bibles were housekeeping documents, often compiled by junior staff or long-suffering script editors who knew the one true rule of television: continuity is king.

As TV shows evolved from disposable crime-of-the-week fluff, the bibles grew too, fattening up on character arcs, lore dumps, and internal logic so brittle it could snap under the weight of a single Reddit theory post if Reddit had been invented back then. Star Trek offered the original blueprint for how to build a sprawling, shareable, infinitely expandable story universe off a show bible.

Gene Roddenberry didn’t just pitch an idea for this one white guy getting laid in space. He handed NBC a fully loaded narrative toolbox that writers still use daily, decades later. The Star Trek series bible, (some of the later ones are downloadable here), laid out everything: the tech, the tone, the Prime Directive, which aliens were sexy, and which plotlines were banned because they made Spock feel weird.

But Trek was still a problem-of-the-week show, and every problem had to be solved in 48 minutes. One of the first truly modern story bibles was written for one of the first truly modern TV shows with a multi-season meta-arc.

Buffy. (Yes, there were others, but I want to talk about Buffy because I miss the 90s.)

The writers’ bible for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which, annoyingly, has never been released in full because God and his IP legal team hate fanfic writers, was the backstage scroll that kept everything tickety-boo. It tracked character arcs, supernatural rules, Hellmouth geography, who was sleeping with whom, and whether Giles was emotionally available this season (answer: never, and also always). It defined the show’s internal mythology, its emotional logic, and scaffolded its freak-of-the-week structure into something much grander: continuous weirdness with purpose.

Buffy didn’t just slay vampires; she killed the idea that episodic TV couldn’t do long-form storytelling. That leap, from stand-alone monster punchfests to extended and layered emotional arcs, the A-Team with the undead and all the feelings, demanded that the writers keep track of both arc and angst across years, not minutes.

As a guy who coughs up trilogies getting out of bed in the morning, I’d often wondered if I should use a bible to keep track of my various series. I was forever getting my Lonesome Jones mixed up with my Tusk Musso. (A deep cut for the fans there.) But I’m lazy. And easily distracted. And did I mention how lazy I am?

But other writers were all over it, especially the fantasy epic nerds and grimdark trilogy lords. They saw what the TV folks were doing and said, “Yes, that. But with more incest and horses.” Series bibles seeped into prose fiction, comic books, games, and your cousin Darryl’s really elaborate D&D campaign that’s been running since 1984.

When I sat down to write World War 3.2, I thought it would be the bridge book in a trilogy. By the time I wrote the last infuriating cliffhanger, I knew that was bullshit. I’d advanced the plot by about three days. Some of the main characters from WW 3.1 didn’t even get a look in, and the idea that I could wrap it all up in one more book was risible.

I wasn’t even sure what storylines I wasn’t even sure about. Did I ever get around to explaining what happened to J. Edgar Hoover? Have I already made that ‘How is Keith Richards still alive in 1954?’ joke?

For the first two trilogies (Weapons of Choice and Stalin’s Hammer), I winged it. I had a sense of where the overall narrative was headed, but the characters had a tendency to hijack the story. (Example? Dan Black and Julia Duffy were never supposed to get together. They just happened to cross paths in Weapons of Choice, and a page later, I’m like, “Whoa, you two. Get a room!”)

That kind of organic chaos is part of the fun of writing a novel, but it doesn’t scale to a nine-book arc with dozens of narrators spread across multiple continents and decades. My previous hack, keeping a single note on my phone, wasn’t working anymore. The alternative, training an AI on the series so far, was… problematic. Not because I’ve declared jihad on AI. After all, they’ve already stolen everything I’d ever written. I figured that giving them another look at my books so they could answer questions for me, serving my ends, and not the sticky-fingered billionaires, couldn’t hurt any worse. But, as I explained in my accidental email yesterday, GPTs don’t retrieve facts the way a search engine does. They predict/guess.

So, the Axis of Time GPT I built for myself insisted that the main character was a Matthew Kolhammer.

His name, of course, is Phillip Kolhammer. He’s the beating heart of the whole fucking series. There’s no Matthews anywhere near him. Yet the bot spoke about “Matthew Kolhammer” with the calm assurance of a $10K-a-day barrister reciting precedent.

So, a week ago, I made a call. A story bible it is then. But this time, I’d build something different, something more like an old HyperCard stack.

The Tools: Obsidian and the Zettelkasten Method.

Honestly, I didn’t intend to go down a YouTube rabbit hole in the Under-Realms of the Note Nerds, but here we are. On Monday morning, frustrated by my inability to get to Apple Notes to work the way I wanted, I typed an innocent query into Google.

“Alternatives to Apple Notes”.

Oh boy. Late Monday evening, bleeding from the eyeballs, I finally retreated to the world of real things. In the course of my personal odyssey, I, too, had become a Note Nerd, specifically an Obsidian geek and a Zettelkasten sicko.

I’ll try not to bore you with the deets, but there will be deets.

Let's take that weird German thing first. Zettelkasten translates as slip box. Think of the old library card catalogues of yesteryonks, those big wooden cabinets in your local or uni library, each drawer stuffed with yellowing index cards and the faint whiff of despair. Each card held a book’s vital stats: title, author, subject, and a call number to help you find it (or pretend to, before slinking off to nap in the stacks).

That was knowledge, alphabetised and obedient.

Zettelkasten is like a card catalogue that went to Burning Man and came back polyamorous and full of theories. Zettelkasten isn’t about storing information. It’s about provoking insight. It’s like Tinder for thoughts, designed to create intellectual hookups you didn’t see coming.

Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist and the patron saint of notetakers, developed this method to write over 70 books and 400 articles. The method? Write each thought on its own index card, give it a unique ID, and cross-reference like a motherfucker with every other thought you ever had. Very soon, your pile of slips evolves into a thinking machine that connects ideas you never realised were related.

Okay, you still do the thinking, but the thinking machine part arrived with the silicon age.

Apps like Obsidian now do the heavy lifting of connection, but the principle remains the same: break your ideas down, link them up, and let your archive start inspiring you.

For a screenwriter or a novelist with a long-running series, filling an app like Obsidian, or Notion or whatever, not just with facts about your story but with ideas about it too, and then hyperlinking them all together, creates a story-world nervous system. It can answer simple queries about what this character did in that scene. But it also starts sparking connections between the thousands of ideas that undergird even the simplest book.

Importantly for some folks, it’s not AI. It won’t converse with you about your story, and it won’t make up a bunch of nonsense about that story either. It does the retrieval, and you do the thinking.

So what went into mine?

(And remember, these things are incredibly personal. So yours, if you decide to make one, for your own book, your hobby, your study or whatever, will be very different.)

Building the Cast

My first order of business was simply to catalogue the characters. This was no small feat. This series has been running for twenty-plus years. Characters come and go, and when they go, it tends to be in a gigantic explosion.

But then some come back! And we retcon that explosion as a cunning distraction/false flag operation/ooh-look-over-here-at-this-shiny-narrative-development-and-pay-no-attention-to-that feeling-of-cognitive-dissonance.

The Story Bible helps me reconcile what’s happened already with what’s coming next. Do you want a technical note arising from that? Character biographies are about their history in the story so far. Character arcs are about what I plan to do with them going forward—all the way to World War 3.8.

Each character needs an arc, and every arc needs to be tracked. Some intersect, some run parallel, and some detonate when they collide. The Story Bible lets me see them all without having to hold them all in my head.

Structuring the War/Culture War

Once the characters were in place, the next step was to impose structure on the story itself. Weapons of Choice wasn’t just about sending an aircraft carrier battle group from the future back to kick Hitler’s butt. It was about sending a lot of uncomfortable ideas about, say, diversity, equity, and inclusion back to the 1940s to see how that turned out. In the Story Bible, that means tracking a lot of conflicting ideas and straight-up conflict.

It meant deciding: how far do the Soviets advance in Europe? Do they reach the Atlantic? Do the old tycoons and robber barons of the 1950s try to stop the technologies and industries of the future from eating their lunch?

The meta-arcs are where it gets really tangled. These are the storylines that span the entire series and involve multiple characters across decades. Mapping these out ensured that no single book collapses under too many storylines, and that every character’s journey contributes to the larger adventure.

But it also means keeping track of the little things, like what happened to Jack Kerouac when his books were all available before he’d written them. How does young Elvis react to finding out how old Elvis died? Can the Beatles become the Beatles if they don’t grow up poor in war-ravaged Liverpool? Each of those ‘ideas’ gets a card and links out to any other ideas or characters that are relevant to them.

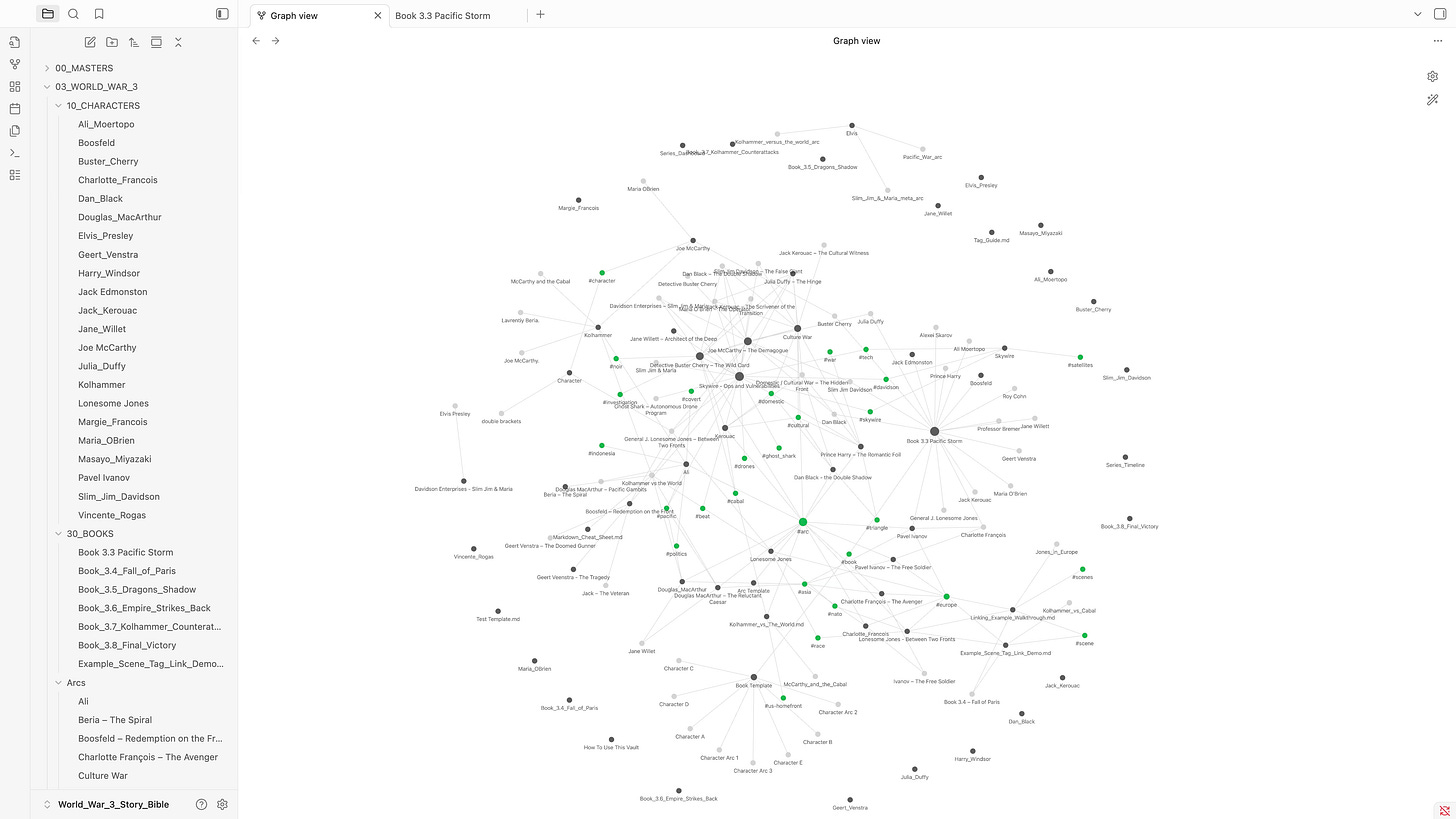

At any given moment, the web of connections can be viewed as an actual web. (Caution, there are spoilers hidden away in this image. And the links are unfinished.)

Finally, building this thing was as much about training myself as it was about scaffolding the books. I had to learn Obsidian, Markdown, linking, tagging, templates, YAML metadata. I had to get comfortable with the graph view, seeing my characters and story arcs as a web of nodes.

In other words, I had to professionalise my process, thirty years into my book-writing career. Better late than never, I suppose.

Will it help?

I’ll let you know in about a year.

For now, it’s time to stop faffing around with the apps and start writing some ‘splodey. If you want to get in on the latest while it’s still discounted and available outside Amazon for another week, this link will hook you up.

Oh, and if it feels like I’m avoiding engagement with the wider world at the moment, you'd better fucking believe I am. What a depressing shitshow.

widely unread personal blog Is a bit harsh should be Read by a special selected few

It's fascinating stuff. Who knew writing was so hard? (Slams bunker door and sets timer for Nov 2028) And look, I know you're busy but if you could see your way clear to a story in the "angry anthropomorphic goose" universe, I'd really appreciate it.