“You’ve written, like, a page or two in every one of these notebooks,” she said.

Oh, great was the shame of it.

Not guilt. Guilt, to borrow from John Bradshaw, merely tells me I've done something wrong. But shame says there is something wrong with me. I could feel that wrong in the slow heat creeping up my neck and spreading across my face.

My daughter was right.

There were nearly a dozen notebooks on my desk, the snow-white glistening tip of an iceberg-sized collection, I can assure you. Every one of them had at least a single page of handwritten notes scrawled inside - and never more than three. It was as though some other me, the disorderly imp and trickster, irked by the neat stacks of Moleskines and Field Notes and Leuchterm journals, had thought not to destroy them but simply to disfigure them. And why not, since the object of such a collection was surely ornamental, not practical?

I have a little problem.

We all do, but this is my problem. There are many like it, but this one is mine.

It’s not specifically about notebooks.

It’s more about… stuff.

If happiness is not “having what you want, but wanting what you have”, my love of certain stuff would fill a thimble with an ocean of having and loving.

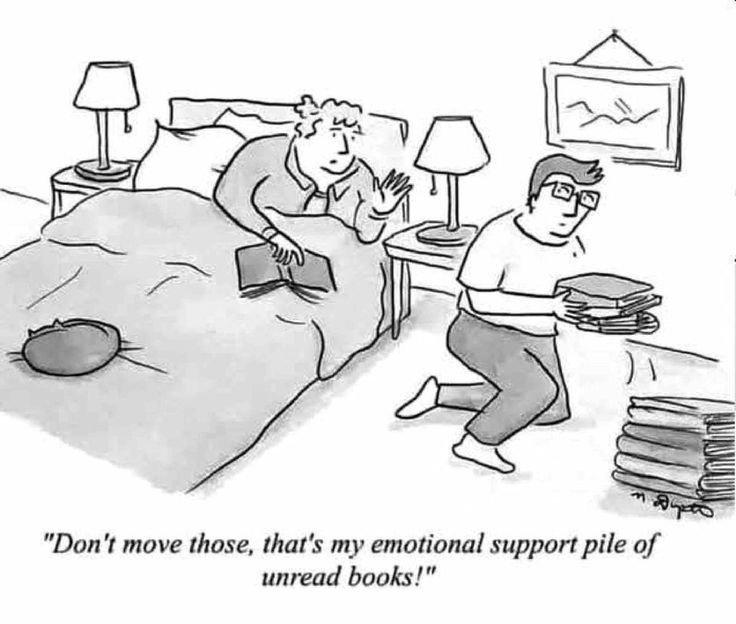

Don’t judge me. I’ll hazard you’re no better. Why, what’s that I spy behind you? It looks to me like… not a stack of unread books but an entire library of them. Or perhaps not books but rather shoes, or stamps or porcelain tea cups.

For me, it’s books in general and notebooks in particular.

I feel like I am one of Virginia Woolf’s narrators in The Waves, “always going to the bookcase for another sip of the divine specific… When I cannot see words curling like rings of smoke around me I am in darkness—I am nothing.”

Or at least nothing that couldn’t totally be improved with the purchase of a stupid thousand-dollar digital notepad.

This started earlier this week when I received an email from the Irish writer Dave Gaughran reviewing his Remarkable 2 digital notepad after 500 days of use.

I truly, madly, deeply wish I had not opened that email because now I want a stupid thousand-dollar digital notepad, too. Yes, I could get it cheaper than this. But, you know, accessories. And yes, I could also claim the cost back on tax because, you know, work expense – a completely legitimate, not even marginally dubious work expense totally incurred while earning income, and not at all while holding back the existential darkness or something. Not even a little bit.

But should a guy whose desk is buried under neutron star densities of not entirely unused paper notebooks really be spending money he does not have on a ridiculous sci-fi notebook he does not need?

Spoiler: no! No, he should not!

But this is the flaw in the theory of ‘existential having’, which Susan Fournier and Marsha Richins define, in the Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, as “the need for some possessions to ensure survival.”

It absolutely feels like I need this thing to survive.

I don’t, of course.

So why do I feel it so urgently?

Fumio Sasaki, writing about Japanese Minimalism in Goodbye, Things, pondered the purpose of owning “so many things when we don’t need them”. He thought the answer quite clear. “We’re desperate to convey our own worth, our own value to others. We use objects to tell people just how valuable we are.”

But as neat as that sounds, it doesn’t click perfectly into place for me. I don’t care who knows whether or not I own a thin slab of brushed steel and silicon that “feels just like paper thanks to its textured display surface and incredibly responsive Marker.”

I’m sure, too, that you don’t care who knows whether or not you just added another half dozen never-to-be-read titles to your teetering pile of previously unread books.

There’s something deeper at work.

I sometimes sit in my library and allow my gaze to wander over the volumes on the shelves, knowing that at least half of them remain unopened, let alone unread, and I care not at all. The Japanese have a word, tsundoku, for the practice of collecting books and not reading them, but I’m not sure whether they have a word for the feeling such a collection evokes.

For me, it is the feeling of possibility.

It is always possible that I might get up from my chair and read that signed copy of Peter Robb’s Caravaggio biography that has been patiently waiting on me lo’ these many years. It’s possible I might finally get around to pulling down Christopher de Bellaigue’s The Lion’s House or Suzanne Loebl’s America's Medicis.

But probably not today.

Today, I’m telling myself that I can buy the stupid digital notebook sometime in the future after I’ve written the five unwritten books on my to-do list and made so much money from them that I physically need to get rid of a thousand bucks as quickly as possible in case I trip over all the dollarydoos lying around my mansion and do myself an injury.

It’s an old trick I play on myself.

Because gratification delayed often segues into gratification denied.

I think it helps me get past the pain point of my particular problem. Agency.

I don’t buy these things because I need them to convey my worth to others, as Fumio Sasaki would have it. I buy them—I feel the deep and urgent need for them—because having them lets me imagine that, for the briefest instant, I am in control. I am getting what I want from the world, not surrendering what the world demands from me.

In that moment, the possible is material.

Old mate Fumio will have his way in the end, however.

The glory of acquisition starts to dim with use, eventually changing to boredom as the item no longer elicits even a bit of excitement. This is the pattern of everything in our lives. No matter how much we wish for something, over time it becomes a normal part of our lives, and then a tired old item that bores us, even though we did actually get our wish. And we end up being unhappy.

It is both hard to believe and undeniably true that I would come to regret placing that stupid notebook within my possession. That’s why I’m here, talking to you about it, preemptively shaming myself into abstinence.

It’s not just about me, after all.

My daughter really needed a notebook that day, and despite the overgenerous sufficiency of my supply, I was unable to give her one that hadn’t been marred. I doubt I’d have filled so many of the things with feckless scratchings if I’d actually valued them for their simple utility.

So much stuff. Unread books, unwatched DVDs, a computer controlled telescope that has never been calibrated and so many other toys of various genres. Now I am of an age that my partner wants me to surrender much of this stuff ready for either downsizing or my demise. She doesn't want to be left sorting through it. It's a job I must get on to... or I might just read one of those books first.

Reading this has been a kind of out-of-body experience. Especially when you mentioned Field Notes, Leuchtterm and Moleskine. My problem extends to Muji notebooks and those lovely narrow Reporters Note books from the US. And Write in the Rain notebooks. I'm working through about 20 only partially filled notebooks from the last 5 years and distilling them into one called The Blender. The plan was to see if I have actually understood anything coherent and useful in the last half decade. It's a bit like how Large Language Models work in AI but I'm trying to use my own brain to formulate linked ideas or potential narratives to form a conclusion from endless daydreaming and reading. For me, it's similar to your words about 'looking for the feeling of possibility.' I feel a whole lot better for reading today's missive.