Sometimes, needing inspiration, I’ll hang out in a bookstore. Anyone can do this, of course, but for writers, time spent lingering between the stacks is never wasted, even if you don’t succumb to the urge, ever dormant, always lurking, to add to your unread stack of shame. In a bookstore, you are surrounded by possibility. All those titles. All the time that went into creating them. All the time you could enjoy reading them. All the paths you could take through the forest.

A while ago, I noticed that one of my old familiar paths was… fading. Sort of disappearing into the old growth and the new.

I’m a nerd. I like to lurk in the genre aisles, which used to mean science fiction and fantasy, but increasingly more of the latter than the former. Much more. From the evidence of the shelves in both specialist and mass-market bookstores, fantasy has triumphed. At a guess, it seems to outsell sci-fi about ten to one. You can still get all the big honking starships full of massive grunty space marines you want online. But in the world of paper books on wooden shelves, it’s dragons and unicorns, or get the fuck outta here.

As a guy who likes both forms and has written in both genres, it makes me a little sad to see one disappear, and I’ve been wondering why readers have abandoned the stars for about a year or so now. I could toss off half a dozen reasons without much thought, an obvious being a gender split. Women readers far outnumber men (sorry, this is a stone-cold fact of the publishing industry) and whole sub-genres of fantasy have arisen appealing directly to female audiences (yeah, okay, this is more in the way of being my take on romantasy).

But I read something recently that had nothing to do with publishing or unicorns or gender theory, which shook up my understanding of why I can’t buy a decent space marine adventure in paperback.

Rosie Spinks, a writer I’d never heard of until this week, dropped an essay on Substack that got me thinking. Indeed, it fucking Spinks-pilled me. She argued that we're living through a collapse - not some exciting Day After Tomorrow-style cinematic catastrophe, but a slow unravelling of all the stuff that makes modern life tick along. At least for those of us in the first world. You know, the basics: how we eat, where we live, what makes us feel safe and happy, who we think we are. Writing after Trump's win, (which, don’t worry, I’m still not going to talk about) she describes living in two worlds at once. First, the world of "There," the sci-fi future of endless progress and tech solutions we all grew up believing in, and "Here," where we're starting to accept things might get worse before they get better and to be honest, they’re probably not going to get better at all.

Reading this, something clicked about the fantasy-heavy shelves I’d been puzzling over in Dymocks and Pulp Fiction. Sci-fi has always sold us the dream that human ingenuity and better tech would fix everything - that's pure "There" thinking, in Spinks' terms. But what if people just don’t believe that anymore? What if they're looking for different ways to imagine what's possible?

Fantasy, with its circular seasons and cycles rather than straight-line progress, its emphasis on small, often primitive communities, and its comfort with natural limits instead of technological efforts to blast through them, might just be better equipped for the world Spinks is describing. This world, ‘Here’, is one defined and limited by the gradual unravelling of our "normal modes of sustenance, shelter, security, pleasure, identity, and meaning."

It’s a world that might prefer stories about finding meaning in simplicity, about the importance of your neighbours over some distant system, and about old knowledge being as valuable, if not more so, than the latest Neuralink update.

Spinks defers to another author to explain the emotional undertow of experiencing such a transition:

The writer Jack Self summed it up much better than I can: “living through collapse isn’t a factual statement, but an emotional one. It feels like we are approaching the end of a specific social contract. Modernity is a project founded on patriarchal domination, on linear time, infinite extraction and unstoppable accumulation. In its five centuries, it has evolved into such an unnatural paradigm that it now only survives through extreme and perpetual violence; perpetrated indifferently against both humans and non-humans alike.”

Perhaps, then, readers aren’t sniffing sparkly rainbow unicorn farts to get high and escape an irradiated techno-dystopian future. Maybe they're just looking for stories that help them wrap their heads around a future they can feel coming harder and faster all the time, no matter who they vote for. From that angle, fantasy taking over the shelves isn't just a publishing trend - it's human beings, the one true narrative species, looking for the kinds of stories that make sense and offer comfort right now.

When you dial down into what Spinks is saying about this shift in how we see time and progress, parallels start to resolve. She talks about people losing faith in what she calls "There" - that world of infinite progress where every problem had a technological solution, preferably a big honking space gun.

But it's when she starts unpacking how our "normal modes of sustenance, shelter, security, pleasure, identity, and meaning" are breaking down that the fantasy connection really clicks. Because fantasy, especially the stuff selling right now, is often about worlds where meaning comes from being connected to place, to land, to community, to ancient wisdom. It's about characters plunging their hands into the ground to figure shit out when all the old certainties and high palaces have crumbled.

How many fantasy protagonists have had to learn some old magic, rediscover lost knowledge, or tap into ancient wisdom to save their world? Do people sense that’s what’s coming for us? Not a future where we can fold space with the awesome power of our antimatter drives, but one where knowing how to grind millet with stones or weave a half-decent fishing net might be the magic that saves the village?

When Spinks writes about millennials living their whole adult lives under this "spectre” of things not working anymore, it's like she's describing the emotional landscape of fantasy. In The Lord of the Rings people live in the shadow of a fallen golden age, dealing with the mess left behind by ancient mistakes.

There's also a parallel in how Spinks discusses the rejection of "infinite progress and wealth." She notes that life may become "less concerned with status, and more with sustenance." This maps neatly onto a common fantasy trope: the rejection of industrial/technological power in favor of more harmonious, if materially poorer, ways of living. Consider how many fantasy stories end not with technological triumph, but with characters choosing simpler ways of life or learning to live within natural limits.

I’m not saying I dig any of this. I fucking hate it, seriously. And Rosie Spinks certainly isn’t making this argument. She’s got something way more important to do. But I like to pretend to myself that our favourite stories are still important, and I can’t help but feel that there is a narrative truth waiting to be found at the edge of her essay.

One telling point arrives when she discusses Aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta's concept of being "a participant in a culture of transition" working on a "thousand-year clean-up." Fantasy, of course, has always been comfortable working with deep time and generational responsibilities, unlike the best sci-fi, which tends to focus on current affairs wrapped in figure-hugging future-skivvies.

You can see how this plays out across two recent series. N.K. Jemisin's Broken Earth trilogy is set in a world where ecological catastrophe isn't some future threat - it's Tuesday. Her characters don't get to solve climate change. They just have to figure out how to live with it, how to build communities that can weather the next disaster, and the next, and the next. Now, teleport over to something like Kim Stanley Robinson's Ministry for the Future. Good clean fun, brilliant stuff, beaming in directly from the Golden Age when we could totally fucking science our way out of a climate crisis if we were just smart enough, if we just get the right people in charge with the right tech and the right plans. It's a seductive idea. But looking at those fantasy-dominated shelves, I'm not sure readers are buying it anymore. At least not in paperback. It's pure "There" thinking.

When Spinks writes about people who "intuitively sense that the current system is irrevocably broken," she’s grappling with the world of real things, right here and now. But she also explains, I think, why so many readers might be drawn to fantasy's common theme of living in a "broken" world rather than sci-fi's typical narrative of fixing systemic problems through technological advancement.

It’s not that we don’t believe in the future any more. It’s that we don’t want to.

We can’t.

Not that version of it anyway. The one with the antimatter drives and the neural uploads and the Mars colonies. Fuck no, especially not your Mars colony, thanks, Space Karen.

What's the point of dreaming about folding space when you're worried about keeping the lights and heating on? I suspect that what readers want now are stories about how to live through the long night, how to keep a hearth fire burning, literally, how to remember the old songs and how to sharpen a fucking blade.

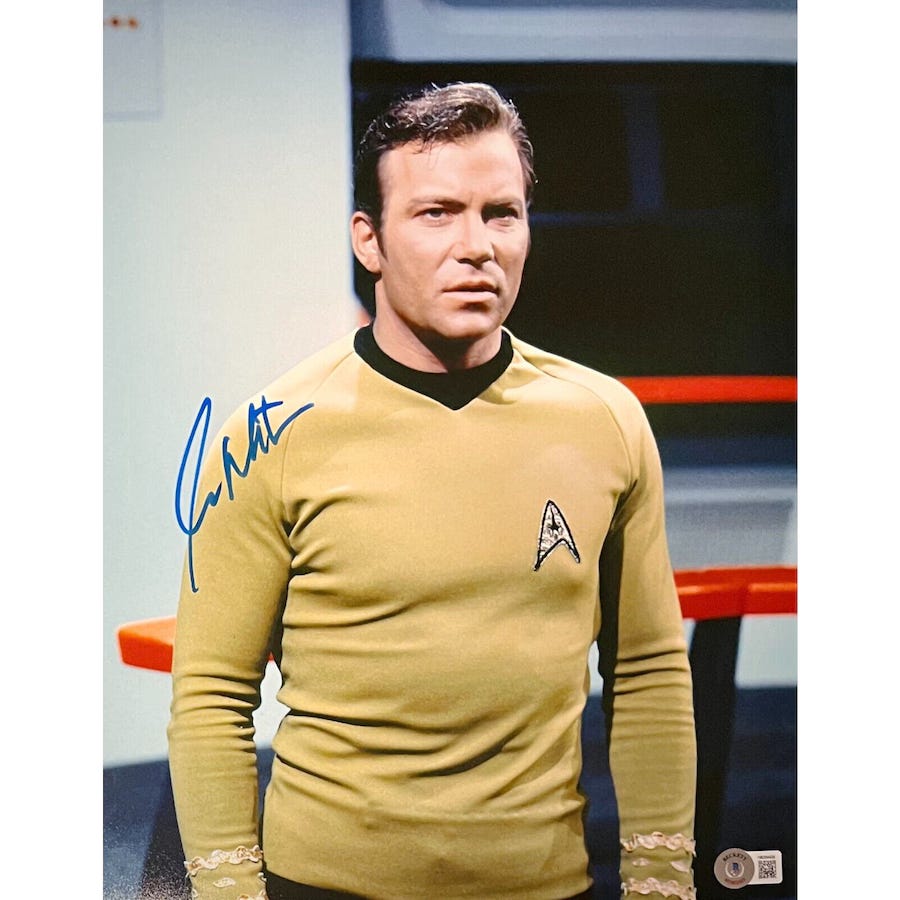

While we’re on books, allow me to segue super fucking smoothly to this little ripper. I’m trying to be helpful, rather than angry at the moment. So I pulled this together last week and I’ve got it at half price this week.

It’s everything I’ve learned about killing the procrastination demon.

It’s on Amazon and yes, yes, I know, some of you hate the Beast of Bezos. I understand.

If you simply cannot come at the idea of even going there, but you need this book, let me know in the comments. I’ll look after you.

Gimme more space operas with kickass female spaceship captains! Ones who are heading to Mars to kill the Space Karen droids.

Over the last 50-odd years, the fact that space travel to anywhere survivable is essentially impossible has gradually seeped into our collective consciousness (even if Elon Musk hasn't realised it). Only the old can remember the moon landings, and only the very old can remember Sputnik. Meanwhile the physicists have cut off every plausible avenue to FTL travel.

That understanding turns large sub-genres of SF into fantasy, set in an impossible future rather than an impossible past.